Making Tough Decisions as a Smallholder Farmer

Last time we heard from Amim, he was in a dilemma, and facing a shortage of cash. He needed to travel to a nearby town to collect fees he was owed for a building project that he was unable to complete because he needed to take his son to the hospital. He also needed to take his newborn nephew, who Amim and his wife Husna recently adopted, to a hospital in another area of Mbeya for his check-ups. And finally, he needed to continue working in his rice fields to ensure a good harvest, which in turn would help his family cover their financial needs for the next year.

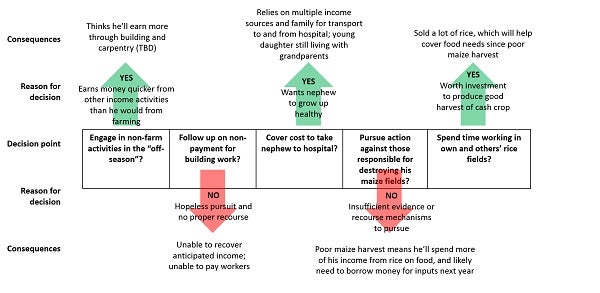

At the brink of deciding how to use his limited time and resources, Amim and his wife opted to take their nephew to the doctor every month. Their nephew is now healthy and well-nourished for a baby of eight months. Amim and Husna can rely on casual work in the fields or one of their numerous other businesses – tailoring, selling sodas, fixing motorbikes, construction – to cover Husna’s trips to the hospital with the baby. For the return trip to their village, Husna typically relies on her parents, who live near the hospital, for the fare.

Amim also chose to invest his time in work in the rice fields, which resulted in a good harvest in May and June. He also farmed in his maize fields, but a cow being cared for by pastoralists destroyed two acres of his crop. Since he had no evidence of who was at fault for the destruction, he had no recourse in the matter and received no compensation. Therefore, despite the good rice harvest, Amim knows he may come up short in the coming year. Typically Amim uses income from selling his maize harvest to cover his family’s food supply for the year. Without this money, and having already sold all of his rice allocated for selling, he anticipates needing to borrow during the next rice planting season to purchase sufficient seeds and fertilizer to produce a good harvest.

Finally, Amim chose not to pursue his case of back payments for his building work. He told us he felt powerless in the situation, with many people vying for the money since it was a government project. As a result, the school director paid someone else the fee to finish the construction. Amim was never able to pay his workers for their contributions to the building, let alone cover his own costs.

Despite the recent challenges with building work, Amim has chosen to pursue more of this type of labor, as well as carpentry, in the farming off-season to earn additional income. While he has fields where he could plant off-season crops such as African eggplant and other vegetables, the climate is hotter and harder to work in and the number and types of crops he can grow yield lower returns than rice and maize. Amim said he chose building and carpentry over farming this season because he earns money quicker than he would with farming. However, that is not to say the earnings are large or more reliable. “Farming is hard: you engage in six months of manual labor and you have to work the whole time, whether you have enough food to eat or not. But for other jobs [such as building], you have other people working with or for you.”

Amim’s story illustrates the trade-offs and types of decisions a farmer must make every day and every season. Over the course of a year, his story demonstrates several important things:

- His commitment to investing in his family’s health – whether preventative measures like taking his newborn nephew to the hospital or reactive measures like ensuring his son receives the proper care when he is sick.

- His ability to diversify income sources in order to cover costs throughout the year, although he insists he would rely more on farming if he had sufficient capital to pay for labor, machinery and inputs to ensure a productive harvest.

- His lack of power or recourse when he was not properly compensated.

So what does this view of a smallholder farmer’s life tell us about the financial services he might need? Where government health insurance fails, is another health insurance option worth pursuing? Where his income from farming and other sources do not provide him access to sufficient capital for farming, will a transparent, high value credit source become available? And if he has a problem with a product, what will be his options for asking questions, taking action and seeing results to ensure he does not lose more money? The upcoming publications from the Financial Innovation for Smallholder Families initiative at CGAP will dig deeper into these questions and others in Tanzania as well as Pakistan and Mozambique.

Comments

Finally, a solid review of

Finally, a solid review of the dilemmas and difficult choices faced by ordinary rural people in the developing world. I look forward to reading more... and am off to browse your site to see if you have someone rather humbler than Amin for us to follow.

I am wondering about this.

I am wondering about this. Bails on offseason farming bc it's too hard. Bails on getting paid for building work (which means he bailed on the workers he owed money to) and doesn't finish the job. Bails on pursuing compensation of any kind for the cow damage. Not someone I'd want to invest in - if i had any funds to spare. Life is hard everywhere. in different ways for sure but still hard. this guy seems a bit unmotivated and wanting handouts. even in the west we have to do fundraising for medical bills and many families are going bankrupt from medical debt. I'm sorry for his plight but there needs to be some more personal responsibility here. i feel most sorry for the workers depending on him.

Add new comment