How Social Media Is Fueling Women’s Entrepreneurship in Myanmar

“I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” I was reminded of this quote from Audre Lorde, world-renowned poet and essayist, when I met Thiri Winn Muang, the founder of a small business in Myanmar called Mori Burma, as I listened to her talk about the mission of her business, which sells organic fabrics and clothes on social media.

“I am employing 25 local women in my workshop. We all work together as a family, and I dream of creating a bigger impact with plans like ecotourism in my village so I can employ more women who are until now marginalized and in poverty and help make their lives better,” she said.

I met Thiri on a trip to Myanmar back in February, before the COVID-19 (coronavirus) crisis hit. I was there to research a growing phenomenon there and in other parts of Asia: women’s use of social media to conduct online commerce. She wasn’t the only woman I met who saw this type of informal e-commerce as a way to help other women. Maw Maw Aung, who employed more than 30 women at her fourth-generation lacquerware workshop, Bagan House, expressed the same desire. So did Rosy (Cing Zeel Niang), who sources traditional fabrics from the predominantly female weavers of the Chin tribes for her store, Rosy’s Chin Fabrics.

As an e-commerce entrepreneur myself, I couldn’t help but feel a common thread in our experiences. My own business in India and Hong Kong sells artisanal handbags hand-painted by artists. Like the entrepreneurs I met in Myanmar, we work closely with female artisans to build purpose-driven businesses. However, whereas my company is active on formal e-commerce platforms, the women I met in Myanmar rely largely on social media to market and sell their products, which means their customer engagement is much more customized, they cannot rely as easily on automation and they must handle all shipping and other ancillary parts of the process.

The more I talked with these women, the more I wanted to know about how they were repurposing social media and how their experience differed from mine. While there’s no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic is putting pressure on small businesses in the region and around the world, the long-term trend of women engaging in informal e-commerce enabled by technology seems set to continue. In fact, my most recent conversations with these women reveal that informal e-commerce is helping them to cope with the crisis through alternative revenue streams that can be enabled with technology.

How big is informal e-commerce in Myanmar?

While data on informal, social-media-driven e-commerce are hard to find, there are indications that this is a widespread and growing area of commerce in places like Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan. The conditions in Myanmar enable informal e-commerce. The country has more mobile connections than people, along with a smartphone penetration of over 80 percent, and Facebook is so dominant that it is almost synonymous with the internet. In fact, Facebook accounts for almost 85 percent of the country’s internet traffic. The prevalence of social media may help explain why formal e-commerce, estimated to account for just $6 million in sales in 2018, makes up such a small slice of the country’s $10–12 billion retail market.

Cultural preferences also may play a role in the growth of informal e-commerce. According to the entrepreneurs I interviewed, buyers across Myanmar (especially in Yangon and Mandalay) prefer the convenience, variety and most importantly, the human aspect of interacting with sellers via Facebook Messenger. Shopping via Messenger is such a pronounced trend that when e-commerce business Mogozay offered users discounts to complete self-checkout on the company’s website, customers still ordered on Messenger. As Matthias Low, the founder of Mogozay told me, “There is a big culture of personalized service in [Myanmar]. Hence, completely digital interactions with ‘no service’ element will take time to become ubiquitous.”

Based on our engagements and research, it is estimated that a large proportion of sellers on social media are women, though there are no gender-disaggregated statistics on either formal or informal e-commerce in Myanmar. Wave Money, one of Myanmar’s leading mobile financial services providers, found that many sellers were using its services via agent network and mobile app to receive payments. When the company’s call center interviewed over 1,000 sellers on the phone, it found that more than 50 percent were women entrepreneurs who sold their products on Facebook — so many that Wave Money decided to set up a program for female entrepreneurs.

One reason for the popularity of informal e-commerce among women may be the low capital requirements. Sellers do not need to keep inventory. They can simply aggregate customer orders to then fulfill them through their suppliers (almost drop-shipping). Additionally, they can reach new customers through word of mouth on social media without spending any money on marketing.

How does informal e-commerce in Myanmar contrast with formal e-commerce?

While in Myanmar before the COVID-19 crisis, I interviewed 15 entrepreneurs who sell goods or services over social media, 13 of whom were women. Many of the women I interviewed used social media to source their products, too, not just to sell them. Facebook was the tool of choice for selling products. Viber, WhatsApp and Wechat were common communications tools for sourcing clothing and beauty products from China and Thailand. However, several women created their products in Myanmar using traditional techniques, employing other women. Social media allowed them to grow their businesses and create more job opportunities. All of this suggests that informal e-commerce could be a catalyst for empowering women.

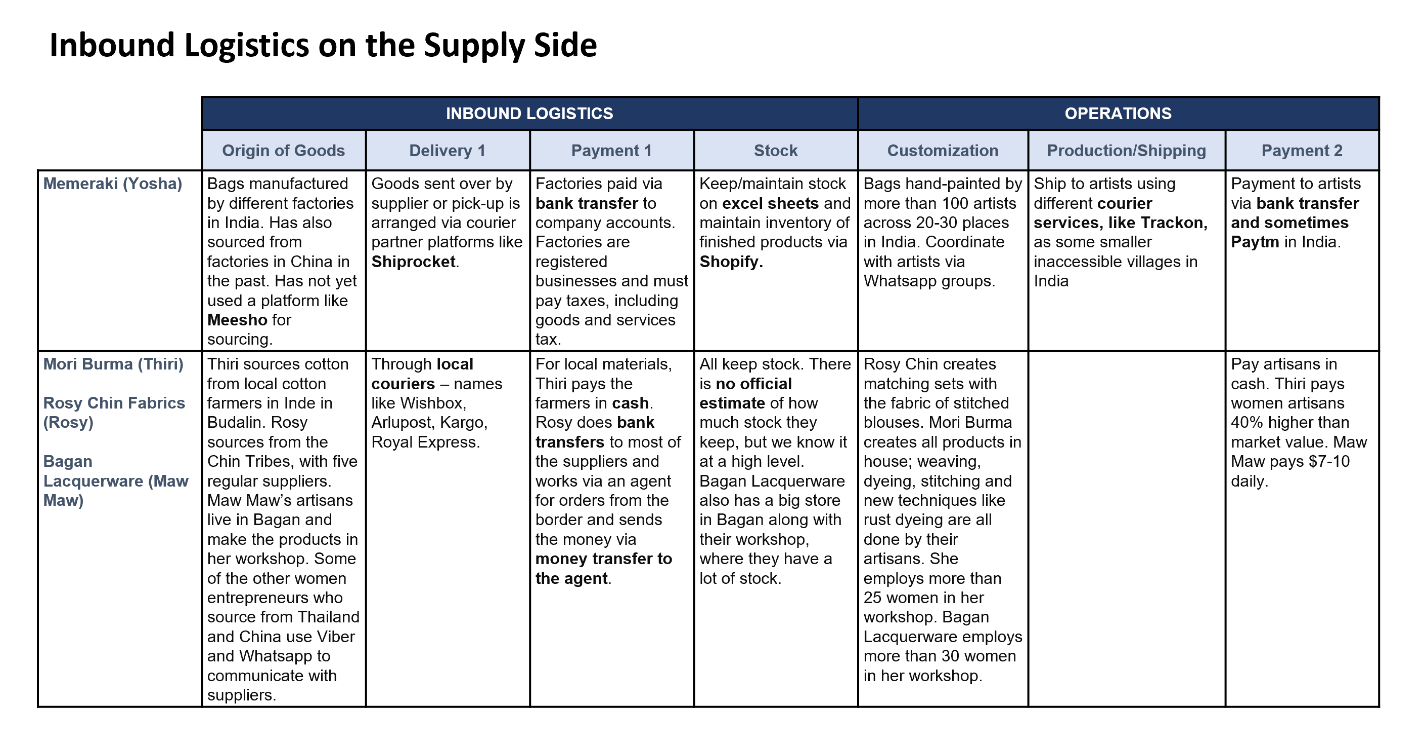

To illustrate in greater detail how informal e-commerce often plays out in Myanmar, the tables below contrast the businesses of the three women I mentioned earlier — Thiri, Rosy and Maw Maw — with my own, which operates under a more formal e-commerce model.

Looking ahead: Technology helping informal e-commerce entrepreneurs to get through the COVID-19 pandemic

Fast forward to today: COVID-19 has impacted livelihoods everywhere, including my business, which has generated almost zero revenue over the past two months. Paying the salaries of our employees and supporting the artists who work with us is the prime concern right now. Technology has again come to our rescue. We have quickly reoriented to organize online art workshops over platforms like Zoom, which are being attended by art enthusiasts across the world, creating new revenue streams for us and our artists.

I reached out to Thiri, Maw Maw and Rosy again to see how they are dealing with this new reality, and they all reported a similar situation. All saw revenues drop to almost nothing and have been using digital technology to adapt. Thiri is looking to conduct online workshops and prerecorded tutorials on new dyeing techniques and textiles through platforms like private Facebook Groups. She also is working to supply raw materials for the workshops. Rosy, who also is a qualified doctor, has turned to online consultations to earn money during this period. She also sells essentials like baby food. Maw Maw closed her workshop last month but has continued paying her artisans from her own savings and is looking at ways that Burmese lacquerware could be taught online. The resilience that each of them has shown during this time and the deep sense of community visible from their efforts to take care of everyone who works for them is a common thread across all their responses.

There is no doubt in my mind that there is an opportunity for more technology platforms and networks to help female entrepreneurs take charge of their lives during and after the COVID-19 crisis, by starting and scaling businesses that lift up other women.

Yosha Gupta is an e-commerce entrepreneur and CGAP consultant based in Hong Kong.

Add new comment