Studying Behavior Can Inform Effective Consumer Protection Policy

Using behavioral research can bring out interesting and unexpected observations about the way people manage their financial lives, which makes it very compelling. But how can these interesting insights from research and field experiments lead to policy change in areas such as consumer protection?

Policy can be a very abstract, macro-level tool, especially on topics like financial consumer protection, where the products are intangible, and positive outcomes not easily definable. In some other areas of development economics, goals are quantifiable (albeit difficult to achieve), such as the Millennium Development Goal to halt the incidence of malaria. Researchers can set a target, take actionable steps – like adjusting the delivery of anti-malaria medications according to recipients’ behavior - and then measure the results. But in the case of a broad, hard- to-define consumer protection challenge like overindebtedness, defining the desired outcome is complicated. Healthy debt levels vary by market, as well as by the context of individual consumers—such as their alternate sources of finance, intended use of the credit, and current and future income potential. While achieving a certain low debt level might be a “win” in one market or for one consumer, that may not be the optimal outcome for others with different needs and opportunities.

Just because turning insights into solutions may be harder with financial consumer protection policy than other topics does not mean it is impossible. CGAP and others’ experience points to several ways in which consumer protection policy can be more effective when it emerges from research that considers consumers’ behaviors and integrates them into policy design.

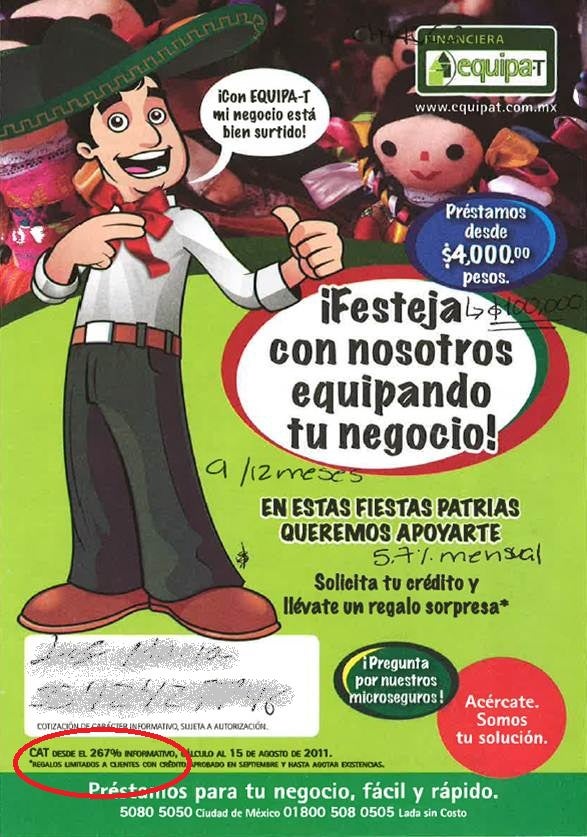

Perhaps the most straightforward use is to help increase consumers’ attention to and understanding of financial products. Information about financial services, such as interest rates on loans or fees associated with opening a bank account, can be opaque, misleading, and not intuitive for consumers. Small tweaks in format, terms, and design can help consumers better contextualize a product’s cost and bring out certain terms and conditions that consumers otherwise do not place significant emphasis on.

A second opportunity for policymakers is to find those cases where consumer protection policies include direct and personal interaction with consumers and design these encounters to help consumers maximize their benefit. Recourse and complaints handling systems are great examples of such an opportunity for behavioral design. These systems involve rules on timing, formats, and steps that consumers and providers must take to resolve problems consumers face, all of which elicit multiple possible “behavioral bottlenecks.” CGAP analysis of complaints systems in several markets found that time, distance, complexity, and trust all act as barriers that prevent consumers from following-through on valid complaints. In many cases, these consumers suffer economic harm as a result. CGAP is working with providers and policymakers to design improvements for these recourse systems with behavrioal research. The goal is to increase the likelihood that consumers will be able to get the support they need from financial institutions when they have a legitimate problem.

Finally, behavioral research methods also identify areas where a different approach is needed to solve policy problems. Sales incentives are a good example of this. Many jurisdictions have tried to influence sales practices by developing complex commission and incentive structures for financial salespeople, hoping to steer sales staff towards product advice that best suits the typical consumer in the marketplace. However, evidence from audit studies across the globe show that many times these incentive structures can be manipulated, or may even lead to sub-optimal behaviors the policies never intended. In these cases, the solution may not be to nudge the market through subtle tweaking of incentive structures, but to explore whether certain commissions or sales practices should be prohibited, or whether product design should be restricted—as was done with payroll lending in South Africa and Mexico.

Policymakers in emerging markets are only recently starting to use behavioral methods to address consumer protection challenges, so the evidence on impact remains limited. As this evidence base grows we expect that there will be a new set of policy tools and tactics that we can start to use to develop good practices for behaviorally-informed consumer protection policies in priority areas such as product disclosure, consumer debt levels, and sales practices. What is needed now is for more policymakers, researchers, and donors to crowd into this space and help grow the evidence base of effective policy design and implementation.

Add new comment