What Can Mobile Money Make Possible? China Has Many Answers

China’s mass-market adoption of mobile payments in recent years has stunned observers. In 2016, more than 500 million Chinese used mobile payments and transacted 97 billion times on nonbank mobile apps. iResearch claims these transactions amounted to more than ¥58.8 trillion ($8.51 trillion) in terms of gross market value, and a recent WeChat usage report by China Research Insights states that an incredible 84 percent of surveyed adults who use the mobile application now feel comfortable not carrying cash. At the heart of these changes is the rise of mobile payments providers and their ability to entice the average smartphone owner to use mobile payments in daily life. How have they done it?

At the recent International Forum for China Financial Inclusion in Beijing, organized by the Chinese Academy of Financial Inclusion, CGAP had the opportunity to hear regulators, development organizations and FinTech companies speak about Africa’s and China’s experiences in financial inclusion. With regard to the African experience, we heard familiar success stories about how large agent networks and telco-led mobile payment providers have improved access to financial services in certain parts of the continent. However, China’s experience stands out as different from the African experience in two ways, which may help explain the success of mobile payments in the world’s most populous country.

The first difference is how China’s mobile payments providers — notably Alipay and WeChat Pay — have leveraged existing financial infrastructure. In Africa, successful models like M-Pesa in Kenya rely on telecom agent networks and infrastructure to reach and interact with customers. In this sense, they have built their solutions alongside traditional banking infrastructure. China’s mobile payment providers (commonly referred to as “third-party payment providers”) have instead built their solutions on top of banks’ access and connectivity infrastructure. Users link their bank card numbers to application-based mobile wallets, so both a bank account and smartphone act as requisite conditions for access.

This arrangement is possible because China enjoys higher levels of bank account ownership and connectivity than many other parts of the world. According to the 2014 FinDex, roughly 79 percent of Chinese had at least one bank account. Because cash-in and cash-out flow through regulated bank accounts, Alipay and WeChat Pay can take advantage of banks’ existing know-your-customer checks. The result for customers is a seamless, remote onboarding process for new mobile wallet users. In terms of connectivity, GSMA estimates 68 percent of Chinese (more than 900 million people) own a smartphone, ensuring a vast market of potential users.

The second difference is that Chinese payments providers tend to view mobile payments services not as ends in themselves, but as means to bring customers into an in-app universe of bundled services often owned, at least partly, by providers. These services — everything from grocery delivery to tax payments — create use cases and build demand for mobile payments. They also multiply the commercial potential of new users. When diverse services are brought into a single payment app, an investment in onboarding a single new mobile payment user is an investment in acquiring a customer across many businesses.

This strategy emerged early on. Alibaba set up Alipay in 2005 to allow Chinese users to purchase items on its Taobao marketplace. Likewise, gaming and social messaging powerhouse Tencent launched TenPay — the payment service behind WeChat Pay — in 2004 to help users complete online gaming transactions. Both platforms were initially intended to facilitate a distinct commercial activity, and neither was mobile-based. For years, these platforms built their user bases thanks to e-commerce and gaming purchases.

Over time, Alipay and WeChat Pay have transitioned to mobile interfaces and have begun targeting China’s rural segment of potential users — a move CGAP explores in a new publication, "China's Alipay and WeChat Pay: Reaching Rural Users." They have also expanded the range of commercial activities linked to their mobile wallets. Mobile peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions and utility payments have combined convenience with novelty for many first-time users. The cultural custom of gifting cash in red envelopes during Chinese New Year has been digitized and gamified. It is now possible for users to send red envelopes — essentially stylized P2P transfers — directly or in chat groups where friends, colleagues and family members could compete to claim a randomized share of the cash gift.

Online-to-offline services like taxi hailing have also proliferated. Paying with mobile wallets has become part of the customer journey for an increasing array of useful products and services. With every use case added, a new icon is imbedded into the WeChat and Alipay interfaces, turning them into so-called super apps, or apps that imbed other apps. Users are able to stay within a single mobile environment from start to finish for any given transaction and across various transactions throughout the day. The simple in-app design creates intuitive user experiences that make the apps feel manageable, even as new services are added.

In parallel to these changes, more and more financial services are being created on the back of the growing amount of data collected on users’ payment transactions and commercial activity on affiliate platforms. Both Ant Financial and Tencent now offer investment, credit and insurance products in-app alongside other use cases. Some of the products are created by Ant Financial and Tencent, while others are offered by third parties using the application as a marketplace.

All of this combined has led to what can be described as Asia’s most transformative digital payment revolution. And as CGAP CEO Greta Bull points out in her blog post, "Financial Inclusion in 2018: BigTech Hits Its Stride," BigTech companies like Ant Financial and Tencent are poised to continue their success this year.

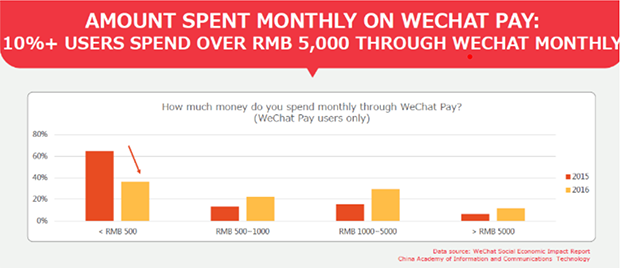

Behind this success is Ant Financial’s and Tencent’s mastery at discovering new opportunities to offer existing users more and better services. Since the beginning, both companies have seen payments as a means, not an end. Consequently, Ant Financial and Tencent are not pure payments businesses. They manage payment services that help users transact across a myriad connected services. This dynamic has helped guide these businesses to finding more mobile payment use cases, in turn creating higher usage among both customers and merchants.

As a result, Alipay and WeChat have, in many ways, become gold standards for mobile payment providers worldwide. For telco or alternative mobile payment models that have done well to provide access to millions of unbanked clients, there are clear lessons to be learned from China’s experience in creating demand-based usage. What can a mobile wallet enable users to do? China has come up with some innovative answers.

Comments

Why not. This time every

Why not. This time every people use mobile phone. Mobile is secure and easy way to use money.

Add new comment