|

The Market: Firms and Products

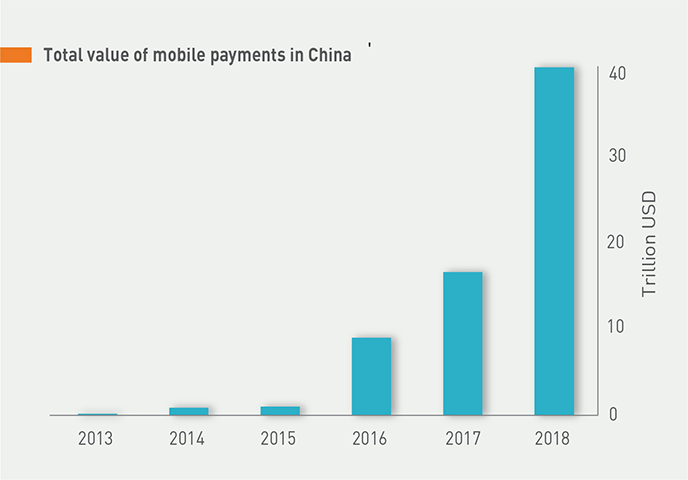

China’s estimated 890 million unique mobile payment users made transactions totaling around $17 trillion in 2017—more than double the 2016 figure. The number of people making mobile merchant payments is expected rise to 577 million in 2019 and to almost 700 million in 2022. Digital payments are becoming so dominant that the People’s Bank of China has had to forbid what it sees as discrimination against cash by merchants who accept only digital payments. This is all the more remarkable because just two decades ago, China was basically a cash economy.

In many regards, this success is thanks to two Chinese tech juggernauts whose brands now reverberate around the world: the e-commerce giant Alibaba and the gaming company Tencent, with its social media platform WeChat.

Alibaba started in 1999 as a business-to-business e-commerce platform that required users to pay via their bank accounts. One of the challenges it faced in this early e-commerce market was the lack of trust in online transactions between strangers. To resolve that issue and drive greater volumes on its platform, in 2003 the company introduced Alipay—an online digital payments solution based on escrow, where Alibaba held the money until the buyer signed off on receiving the goods. In 2008, Alipay officially introduced its mobile e-wallet and launched Alipay’s meteoric growth. While it took Alipay five years to reach 100 million customers prior to 2008, it added 20 million new users in the first two months of 2009. Today, it has 700 million unique users.

Tencent, on the other hand, entered the payments space from a different angle. Founded in 1998, it quickly became China’s leading player in online messaging through its blockbuster chat product QQ. Building on that success, the company pivoted into online gaming—a space that heavily relies on online chat. Today, Tencent is one of the world’s largest gaming companies. To support that business, it introduced online payments brand Tenpay in 2005. The social aspect of its business model remained central to Tencent’s business, and in 2011, it launched WeChat, a smartphone-based social messaging application that became even more popular than QQ. In 2013, it integrated Tenpay into WeChat, creating WeChat Pay—a payments product embedded in WeChat that enables users to send each other money directly through the messaging platform.

These two mobile payments products have rapidly reshaped China’s payments landscape. With monthly active users of over 500 million (Alipay) and 900 million (WeChat Pay), they have created a massively valuable mobile payments market that they completely dominate (93 percent of the mobile payment segment is controlled by the two). More than 20 million users make purchases every day through WeChat Pay, and 200,000 people sign up for the service every day.

Much of this growth has taken place on the back of quick response (QR) codes, which were invented in Japan in 1994 but never really gained traction until taking off in China. WeChat Pay and Alipay introduced proprietary versions of QR codes in 2011 and, by 2016, more than $1.65 trillion in transactions used the codes. Recent numbers suggest that the vast majority of the $5.5 trillion mobile payments made in a year were handled via QR code on WeChat Alipay apps.

Both companies have since leveraged the massive uptake of their app-based online payments products to successfully move into merchant payments. Around one-third of consumer payments in China are now cashless, and three-fourths of Chinese smartphone users made a mobile point-of-sale purchase in 2017 (compared with one-fourth of American users). This is almost exclusively thanks to AliPay and WeChatPay. How did they do it? Let’s get into the details.

Merchant Payments in China: Key Features

Two key enabling factors in China made it ripe for a digital payments and retail revolution. The first is high levels of bank account ownership (79 percent), which served as a foundation for funding the mobile wallets. Alipay and WeChat Pay were able to ride on existing financial infrastructure in the form of bank accounts and bank cards and clearing and settlement systems. In fact, both companies are classified as “third-party payment companies,” which highlights their reliance on an underlying bank account. The second is widespread smartphone ownership, which rose from 29 percent in 2013 to 71 percent in 2016 (Findex 2014; BTCA 2017). Smartphones combined with bank accounts allowed users to easily link their accounts to their phones through an app.

In this environment, Alipay and WeChat made smart choices to drive wallet use. Most importantly, they created a strong customer-value proposition by deploying payments not as an end in itself, but as a gateway to a vast digital ecosystem of products and services. Alipay and WeChat Pay both link users’ wallets directly to in-app retail platforms that also include financial services, such as investment and insurance products, e-commerce services, and convenient solutions for bill pay. Their apps link users’ bank cards to a smartphone application, which in turn enables an endless list of offline and online consumption and bill payment services—from taxi hailing and grocery delivery to utilities and credit card payments, to booking wedding venues and investing in financial products. More than 1 million restaurants, 40,000 supermarkets and convenience stores, 1 million taxis, and 300 hospitals are connected to the Alipay app.

Among many other benefits of this approach, seamlessly integrating ordering and payment helps avoid having to compete with cash. Whereas for an in-store transaction like buying a pizza, the choice between cash and mobile payments is not self-evident, when ordering through this new approach, the payment is already made by the time the pizza is delivered. While cash on delivery is theoretically also possible, it is a clunky option.

To drive uptake, the companies have also created easy on-boarding for customers and merchants. Customers self-enroll through the app, and sellers can start accepting digital payments by sharing their individual QR code even before registering as merchants. This first step lowers the bar for testing digital payments in the business and has helped many make the transition. Initial documentation requirements are minimal: new customers must link their payments wallet to an existing bank card or account, allowing mobile payments providers to leverage existing customer due diligence (CDD) information for that bank account. As merchants’ volumes increase, providers typically ask for additional information to deepen their CDD.

To encourage wide uptake and drive volume, both companies take a relatively light approach to transaction fees, so as to not create the type of pricing or behavioral barriers that can otherwise be a significant challenge. If the merchant’s monthly transaction volume is lower than a certain threshold, Alipay and WeChat Pay refund the commission, whereas merchants transacting above the threshold pay between 0.6 percent and 1 percent of the transaction value. This ensures that small businesses can use the service virtually for free, while it also creates fee revenue from companies who use the service a lot. Like person-to-person payments, merchant payments are free of charge for end customers, though customers must pay a 0.1 percent fee when they withdraw amounts above a threshold ($153 for WeChat and $2,897 for AliPay) from their e-wallets. This fee structure is designed less to generate revenue than to encourage users to leave funds in the wallet and spend them within the ecosystem.

Part of the reason that the Chinese mobile payments giants keep transaction fees relatively low is that they recognize the cross-selling opportunity that comes from other parts of their digital ecosystem. As customers start using their digital wallets as their payments instrument of choice for day-to-day purchases, they also become much more likely to buy any of the myriad other products and services embedded in the wallet. About 640 million people use more than one category of product in this ecosystem, and 190 million use five or more. These opportunities for cross-selling can be significant. For example, Alibaba’s Yu’E Bao grew to become the largest money market fund in the world in just four years, with $233 billion under management, representing 25 percent of China's money market industry.

Another reason Alibaba and WeChat keep fees low is that both recognize the value of the data they get access to and the insights these generate on the preferences of both individual customers and specific segments. These insights can be used to refine sales and marketing of existing products and to spur the creation of entirely new ones, including merchant credit and other financial services underwritten on the basis of the payments and other data collected through the ecosystem. These types of VAS can be powerful accelerators of digital payments by attracting merchants to the platform and generating revenue outside of transaction fees.

The data generated also can be used in other ways. Notably, they are a central enabler of the fundamental transformation of retail commerce that Alibaba founder Jack Ma has labeled “New Retail.” This shift to New Retail relies on data to not only power ever better services to merchants, but to reinvent the logistics systems delivering goods to both merchants and end consumers and to create product development processes that are far faster, more interactive, and tailored to customer preferences than traditional methods. For more on this, see “New Retail Revolution.”

Both companies have also taken a savvy approach to driving consumer excitement. In 2014, WeChat Pay famously created a digital version of the traditional “red envelope” gift exchange to drive acceptance of the payments mechanism. These became an instant hit with consumers and contributed to the service’s rapid growth. Similar products are now available from all of China’s major payments platforms.

Another customer incentive is loyalty rewards, to which Alipay executives give significant credit for driving uptake and volumes. This year, Alipay is offering subsidies totaling 500 million yuan ($73.6 million) for a hongbao (red envelope) campaign to reward customer loyalty. A few years ago, a similar campaign featured incentives such as bus rides, rebates, and even gold. In 2017, Alipay set aside 1 billion yuan ($160 million) in cash-back incentives for purchases made through Alipay to get shoppers to use the service more often. While Alibaba and Tencent initially offered generous incentives to get merchants to go digital, ultimately, rapidly changing customer preferences drove uptake.

Finally, the choice of QR codes as the main acceptance technology has enabled rapid scaling up and widespread acceptance of digital payments. As discussed in “Distribution,” QR codes have many advantages—they are cheap and easy for both customers and merchants to adopt. Alipay and WeChat Pay tested various technologies, including near-field communication, before opting to use QR (static as well as dynamic). Furthermore, the People’s Bank of China announced it intended to regulate QR codes to improve security, and it is creating an online settlement platform, called Wanglian, for nonbank institutions. These moves, combined with a global trend toward standardized QR codes, suggest that mobile payments may soon be interoperable in China.

Takeaways

The Chinese experience illustrates how quickly digital merchant payments can scale if providers get it right. To shift in just a few years from an almost entirely cash-based retail economy to one where the regulator needs to remind businesses that they need to also accept cash is nothing short of astounding. Cash in circulation relative to gross domestic product fell by 13 percent in just four years (2012–2016), and mobile payments volumes are now 50 times that of the United States.

To be sure, this shift has been enabled by a series of contextual factors that mobile payments providers in most other developing countries could only hope for: a high level of bank account ownership, smartphone penetration, mobile internet access, and both financial and actual literacy. Without these factors, it is hard to see digital merchant payments growing as rapidly as they have in China. For more on how these contextual factors laid the foundation for mobile payments in China, see “China's Alipay and WeChat Pay: Reaching Rural Users.”

Providers in other markets can learn from what the Chinese providers did right, including:

- Develop a compelling value proposition by offering a wide range of useful services to both customers and merchants—and by continually widening and deepening the digital ecosystem access through the payments wallet.

- Reduce on-boarding frictions, by enabling self-enrollment of both customers and merchants, increasing the level of know-your-customer standards only as it becomes necessary, and enabling merchants to get set up instantly through the QR code in the app.

- Reduce transaction frictions by using QR codes and highly responsive interfaces, setting initial transaction fees to zero for new merchants and increasing them to modest levels only as volumes pick up.

- Leverage loyalty rewards to shift incentives away from cash and encourage a viral uptake of digital payments through the sheer sense of fun and anticipation around opening your virtual rewards bonus.

- Take a long and holistic view of profitability by treating payments as a driver of indirect revenue today and an enabler of even more compelling offerings in the future, including positioning the company for the coming transformation of retail.

These are things that mobile money providers and other current or prospective players in the merchant payments space in developing economies can implement, albeit in different ways, depending on the circumstances. And they may actually have some advantages of their own; for example, they have a market without existing uptake of bank accounts and payment cards where digital wallet providers have less competition for the mass market and can have the customer relationship all to themselves.

Some providers will bemoan the challenge of doing this with a user base that still heavily relies on feature phones. While this clearly presents limitations, providers should focus on the many things above that they can do even on basic phones—and on having compelling apps available particularly for the many merchants who do have smartphones. The rapid growth of smartphone access worldwide, including in Sub-Saharan Africa where GSMA predicts smartphone use will double to 68 percent of mobile users by 2025, allow for quicker, more intuitive and interactive interfaces.

It is worth noting that even in China, the mobile payments revolution is far from complete. Importantly, rural China has yet to join the digital transformation. A 2016 study found that 46 percent of respondents in northwest rural China had a smartphone, but that only 11 percent of respondents had tried mobile financial services. While these numbers are improving, Alipay and WeChat Pay will need to adapt their approaches if they are to have success in rural areas. That said, Findex shows that the share of people in rural areas of China who have used digital payments in the past year (64 percent) is catching up with the cities, though urban residents still transact significantly more often. For more on mobile payments in rural China, see “China's Alipay and WeChat Pay: Reaching Rural Users.”