Market conduct supervisors and other stakeholders can adapt the materials in this toolkit based on their individual contexts, the availability of quality data, staff capacity and skills, supervisory powers and responsibilities, and concurrent priorities. This section proposes actions for different actors to strengthen market monitoring for financial consumer protection.

Market monitoring by market conduct supervisors

While the toolkit provides high-level general guidance, not all guidance fits every context. Taking the following actions can help you to successfully apply the guidance to your context:

- Assess where you are on your market monitoring journey

- Consider how market monitoring fits into your supervisory activities

- Establish or verify a strong foundation for the use of market monitoring tools

- Select an efficient and effective mix of tools

Assess where you are on your market monitoring journey

A market monitoring journey can evolve over time. To determine where to start or what to do next, it is important to assess your current situation, what you require most, and what is feasible.

1. Take your first step in monitoring

Regardless of whether you already have high-quality data, a dedicated team, or previously allocated budget, start the market monitoring process by adding a market perspective to your regular institution-focused analyses of regulatory reports and by producing market-focused outputs. You may eventually choose to conduct market-level analyses on a regular basis—perhaps even prior to adding analysis as a strategic supervisory planning activity. For example, consider conducting a thematic review with the objective of identifying and assessing a particular consumer risk or issue across financial service providers (FSPs).

2. Integrate market monitoring into your annual supervisory planning

Once you officially recognize market monitoring as a supervisory activity, you can better plan how to use staff and budget and identify gaps in resources and expertise. While you may not initially have the budget to execute planning, planning itself and the results of initial market monitoring activities can help secure additional budget. Supervisory planning can also clarify market monitoring objectives and scope. Your objectives may need to closely align with policy goals (e.g., market integrity, consumer protection) while continuing to focus on consumers. The scope of your market monitoring activities may gradually expand as more resources and data become available. In the initial stages you may solely focus on several consumer or regulatory issues, or products and services within a market (e.g., consumer credit disclosure and fairness by banks, claims response by non-life-insurers). Planning is a necessary step for managing and reporting on market monitoring activities as it ultimately increases accountability and transparency.

3. Build market monitoring activities

Assigning planned monitoring activities to one or more supervisors is another building block of the market monitoring function. While these staff members often have a prudential supervision or institution-focused background, they may experience a learning curve before fully grasping market-level and consumer protection perspectives. Rotating staff members through market monitoring activities makes it easier to identify the best fit for each monitoring function. You can also build specialized expertise by assigning monitoring activities to dedicated staff member(s). This approach balances traditional risk-based supervision with market monitoring in terms of level of effort and resources. Although specialization is required, you can benefit from high-quality integration and coordination between institution-focused supervision and market monitoring. The two-way information exchange ensures that activities inform and reinforce each other.

4. Create a specialized market monitoring team

For market conduct supervisors ( MCSs) that oversee small teams in modest markets, it may be enough to build expertise by assigning market monitoring activities to a specific group of supervisors. However, supervisors that face heavier workloads may find it difficult to carry out both institution- and market-focused activities. In this case, market monitoring may be less of a priority than other projects with consequences that immediately impact FSPs. The lack of a dedicated team can lead to less of a focus on emerging risks and the increased possibility of risks materializing or going unchecked. In most cases it is useful to create a dedicated market monitoring team, even if only a “team” of one.

5. Enhance data analytics capacity

In an ideal world, an MCS begins market monitoring activities with granular, state-of-the-art, almost real-time data; trailblazing data analytics capabilities; and supervisors who are fully adept at handling and analyzing large volumes of data. However, in today’s actual emerging markets, an MCS often begins with limited regulatory data reporting and data analytics capacity. Whatever your context, it is important to aim high and plan for improved data quality and data analytics capacity going forward. Your activities may include assessing regulatory reporting data quality and developing strategies to improve it.

Effective market monitoring for consumer protection purposes begins by implementing the basics (i.e., regulatory reporting), then progressing toward a combination of numerous tools and the more intensive use of supervisory technology (suptech). Where you are in your market monitoring journey influences which tools you prioritize—based on supervisory objectives—and your capacity to begin using different tools to address evolving needs.

Consider how market monitoring fits into your supervisory activities

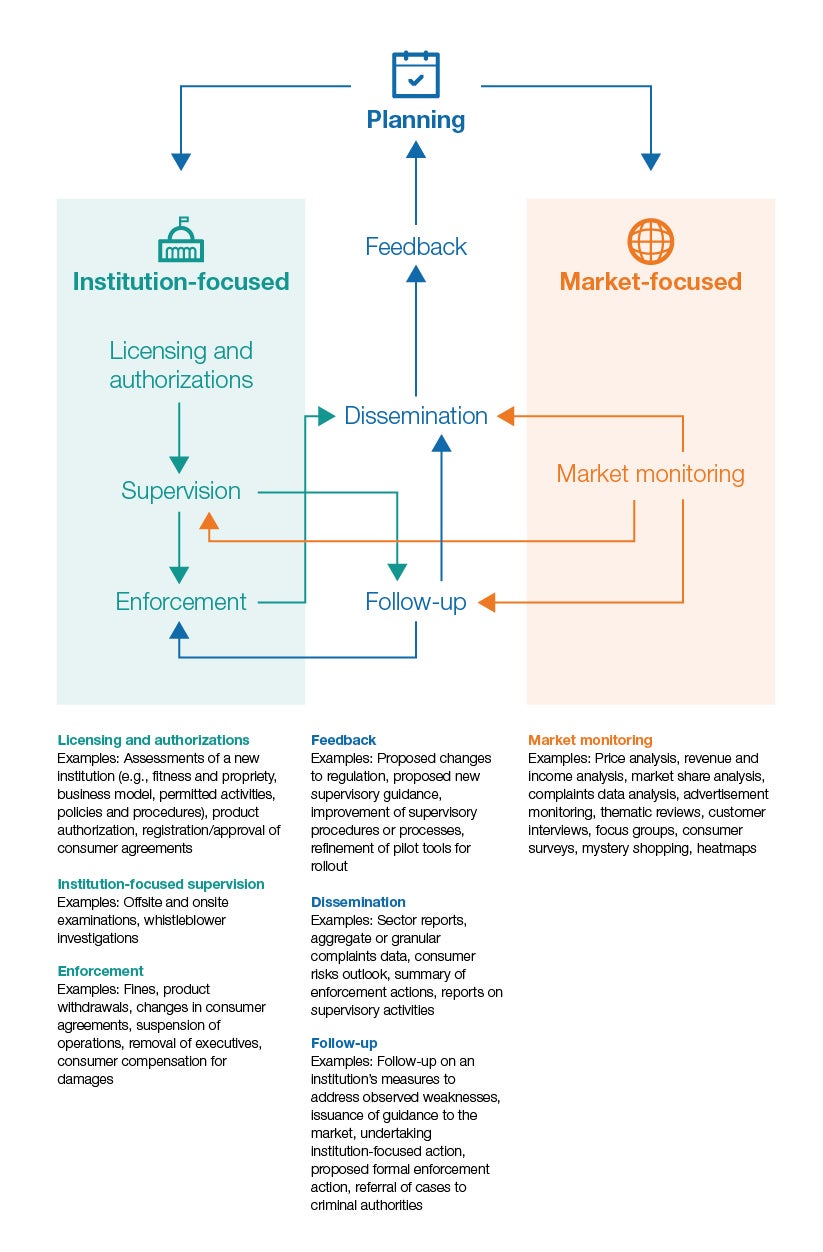

Financial sector supervision exists in two dimensions: with individual institutions and with the market as a whole (or sub-sectors within that market). The following supervisory activities can be carried out in both dimensions:

- Licensing and authorizations

- Institution-focused supervision

- Market monitoring

- Follow-up

- Enforcement

- Dissemination

- Feedback

Each activity involves a range of onsite and offsite tools and techniques selected for a specific task. These supervisory activities are part of a cyclical process that begins with good planning. Market monitoring tools may be used by MCS staff in specialized or dedicated monitoring or research units, staff carrying out macro- or sector-level supervision or analysis, and staff in charge of institution-focused market conduct supervision that need to expand their scope of work by incorporating market-focused activities.

Figure 1. Types of supervisory activities

Establish or verify a strong foundation for the use of market monitoring tools

A strong foundation for the use of market monitoring tools includes an adequate legal mandate to perform market conduct supervision (specifically market monitoring), adequate staff, analytical and subject matter expertise, and high-quality data—especially regulatory reporting data. “Quality” in this case refers to adequate data scope and data types, data accuracy/reliability, and data timeliness and frequency. These elements are crucial, regardless of the mix of tools used.

MCSs are increasingly interested in using new suptech tools and techniques to gather and analyze unstructured, qualitative, and more abundant data. Suptech has the potential to improve market monitoring in many contexts. However, investment in new suptech tools may divert attention away from the need to address weaknesses in regulatory reports –the most important source of data for market monitoring. This is especially true if new tools do not fit supervisory needs and objectives are reviewed in isolation (i.e., without considering how they complement or supplement regulatory reports and other monitoring tools). Indeed, rich findings from other tools are frequently combined with insights from regulatory report analysis.

Regulatory reporting is arguably the most cost-effective data source for market monitoring and is ideally used to the fullest extent. While regulatory reporting sometimes covers unstructured and nonstandardized data, it centers on generating structured and standardized quantitative reports. It is essential to ensure that structured reports are of high quality, regardless of the approach and technology used for data collection. If weaknesses are left unchecked, future investment in advanced tools will stand on a shaky foundation. CGAP interactions with MCSs across the globe suggest that many face severe data quality issues. While we encourage using a mix of market monitoring tools to ultimately protect financial consumers, the foundations of those tools need to be strong. Funders can play an important role in supporting supervisors in emerging economies to improve market conduct supervision.

The strength of regulatory reporting data quality can be systematically tested by:

1. Identifying your policy goals (e.g., those enshrined in laws and policies, such as “protect consumers, especially vulnerable segments”)

2. Identifying the specific supervisory objectives that stem from each goal (e.g., “identify and assess the main risks women face in credit markets”).

3. Identifying the indicators needed to achieve supervisory objectives (e.g., granular gender-disaggregated loan data from all regulated lende

[These three initial steps comprise the mapping exercise, which can be used to assess your data scope and identify your data needs and gaps.]

4. Once you have assessed the adequacy of the scope of your current regulatory reporting data, assess the appropriateness of reporting timeliness, frequency, format, and accuracy.

Upon assessment of the quality of your regulatory reporting data, you may find that you need additional market monitoring tools or to completely revamp your data collection mechanism. A data strategy can help determine which investments to focus on by:

- Identifying your organization’s overall approach to data collection, storage, management, analysis, and visualization, based on a data needs and gaps assessment

- Setting priorities for implementing improvements—from enhancing or completely revamping regulatory reporting to investing in new tools

- For each planned improvement, identifying benefits, limitations, and weaknesses (e.g., of a new tool); analytical and other technical resources to be put in place; and budget and timeframe

Select an efficient and effective mix of tools

As you explore this toolkit you may feel encouraged to adopt a new tool or to improve a tool you currently use. Remember, effective market monitoring always requires a mix of appropriate tools. While each tool brings value, no single tool leads to effective market monitoring on its own. Keep this in mind as you explore the country cases and the single tool highlighted in each one. Market monitoring tools do not contribute to supervisory objectives on their own; they require action based on evidence gathered from market monitoring itself, along with other supervisory tools.

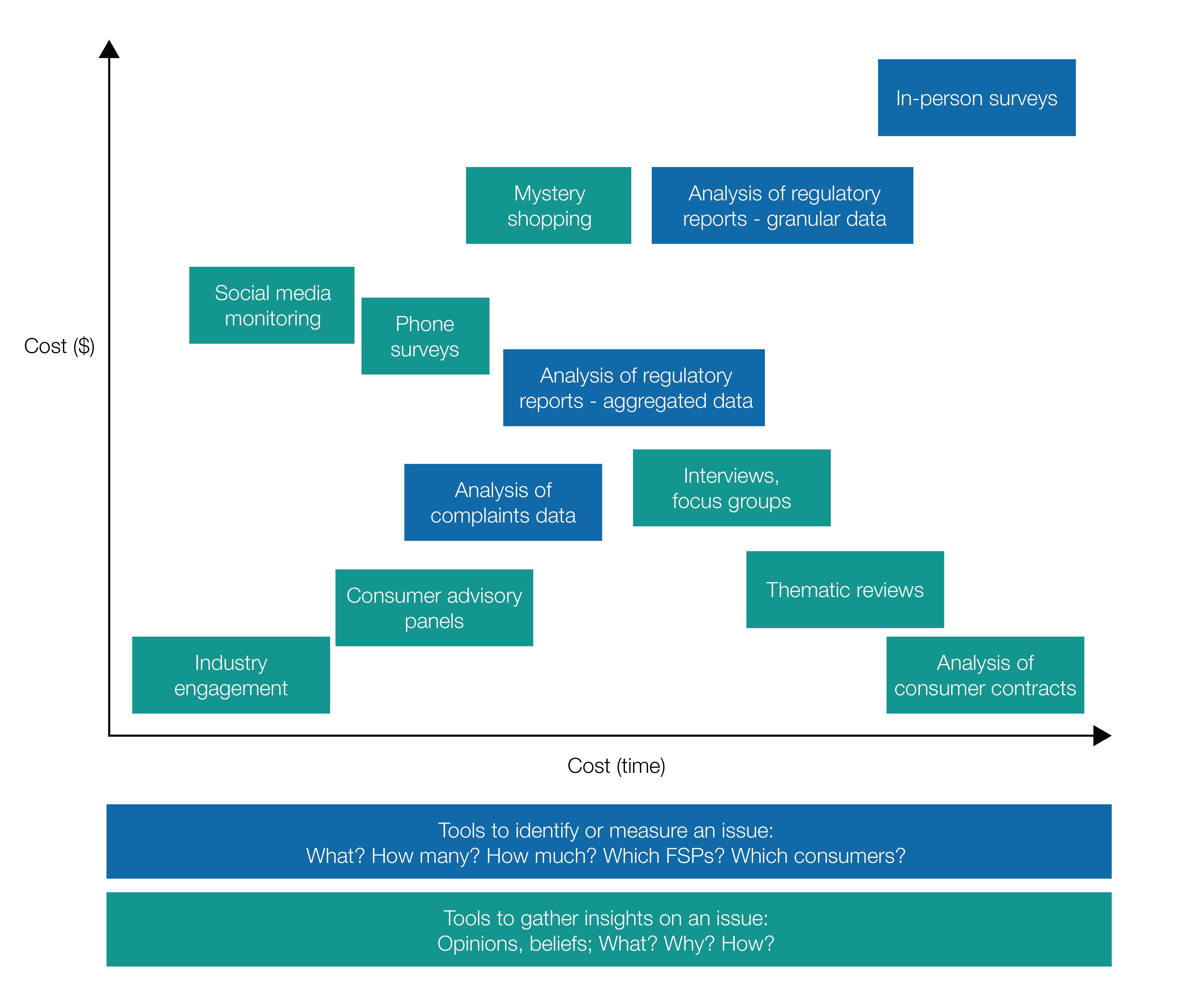

You can build a solid mix of market monitoring tools by considering the purpose and cost of each. It is also important to assess whether your market monitoring foundation is solid enough to support innovative tools that go beyond regulatory reporting.

Tool purpose

Different tools have different purposes, and each tool has its specific benefits and limitations. For example, some help to identify and measure issues while others expedite richer insights on those issues. Each country context requires a different mix of tools, depending on supervisory objectives and factors such as financial and human resources, analytical skills, and legal powers. When deciding which mix of tools to use or whether to invest in a new tool, it is crucial to know a tool’s purpose, benefits, and limitations; how it complements existing tools; and whether the resulting mix aligns with your supervisory objectives. Common supervisory objectives include monitoring consumer risks, over-indebtedness, sales and marketing practices, products available in the market, consumer complaints, gender-based risks, consumer sentiment toward financial institutions, and emerging risks in the market.

Tool cost

The cost of adding a new market monitoring tool to your mix matters. Cost is not only about the financial investment but the effort involved in using the tool. For example, conducting a nationally representative consumer survey about people’s borrowing experiences may provide rich insights for market monitoring but can be time-consuming and expensive. Resource-rich MCSs may be able to conduct such surveys annually but those in developing countries may lack the means to do so. A mix of frequent surveys with a small sample of consumers, mystery shopping to dig deeper into specific issues, and a few in-depth consumer interviews can provide an MCS with significant information that, although not nationally representative, does identify emerging risks, gender-based bias and other types of discrimination, and the root causes of problems highlighted by complaints data.

Figure 2 provides an idea of the relative costs of market monitoring tools. It is important to note that the distribution is different everywhere. The same tool carries varying time constraints and monetary costs in each context. For example, since surveys vary widely in scope, that impacts the price tag and the time needed. An SMS-based survey on an issue such as consumer experience with complaints handling is a relatively inexpensively way to glean rich insights from a large number of consumers. Consumer contracts analysis is another example of a low-cost tool since an MCS only needs to request documents from FSPs. However, if performed manually, it would take numerous staff members many hours to review a few regulatory provisions in a small sample of contracts. If the MCS could use suptech [see suptech FAQ] to automate that part of the job, the tool would become more expensive due to the upfront investment. However, the analysis would be substantially less time-consuming and potentially more effective.

Figure 2. Monetary costs and time constraints of market monitoring tools

Back to top ↑

Market monitoring for other stakeholders

While quality market monitoring should be a core activity for market conduct supervisors (MCS), other financial sector stakeholders can also benefit from (and support) market monitoring.

These may include consumer advocacy groups, FSPs, industry associations, competition authorities, general consumer protection authorities, as well as development funders and international organizations. Each of these have an interest in not only better understanding consumer experiences and risks in the financial sector, but also ensuring that consumers attain good outcomes from their engagement in the financial sector, and that financial products and services are offered by responsible and more customer-centric FSPs that realize the importance of consumer value for sustained business value.

These actors could directly or indirectly benefit from market conduct supervisors that effectively monitor the market and are therefore are able to better understand market developments, to preemptively identify and addresses consumer risks and problems in the market, to communicate market findings and guidance to the general public, and to incorporate inputs and feedback from market monitoring into their regulatory and supervision.

To some degree, quality market monitoring could be considered a shared goal with different actors supporting it in different ways.

Consumer advocacy groups can help customers raise their complaints with FSPs and alternative dispute resolution schemes, push for fair business practices by FSPs, advocate for legal and regulatory reforms, represent and advocate for the rights of vulnerable customer segments like low-income rural women, or sue FSPs on behalf of consumers. Consumer associations can also conduct market research on consumer risks and support public interest litigation. They can not only contribute to improved market monitoring by gathering, analyzing, and sharing data and insights on consumer issues but also benefit from market monitoring efforts that can help them better understand market developments and related consumer risks and act on them. For example, Russia-based International Confederation of Consumer Societies (KonfOP) since 2014 has been publishing regular monitoring reports on the state of the protection of rights and interests of consumers of various financial products in Russia and contributed to identify discriminatory practices in Russia against pregnant women and other vulnerable groups, which were corrected by the regulator.

In Brazil, the consumer association Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor (IDEC) handles thousands of consumer complaints every year and, building on its direct experiences with consumers, is advocating for a bill that would provide fair debt restructuring for over-indebted customers. In Indonesia, the Indonesian Consumer Foundation (YLKI) in 2016 contributed to the drafting of an amendment to a law on electronic information and transactions, which aimed to protect consumers against abuses related to electronic transactions. See Elevating the collective consumer voice in financial regulation for more examples of consumer associations’ actions to support market conduct monitoring.

General consumer protection authorities may have a mandate to push for fair business conduct practices by FSPs or powers to resolve or mediate on individual consumer complaints against FSPs. They may want to monitor the evolution in consumer complaints, as well as FSP responses to such complaints, monitor social media for signs of abusive or unfair practices by FSPs, or monitor unfair advertising practices. Consumer protection authorities with a dispute resolution function will benefit from market monitoring to predict resources needed in the near future to handle disputes from an issue and then to monitor how a precedent decision impacts the market actors’ behavior. For example, Russia’s Federal Service for the Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing (in Russian) monitors market practices with respect to savings products. Peru’s National Institute for Defense of Competition and Protection of Intellectual Property (Indecopi) has set up a specialized monitoring center to collect and analyze reports from consumers on unfair business conduct, including in the financial sector.

Competition authorities may coordinate with MCS to analyze market-level data such as price and product market share through a competition lens. Data-sharing mechanisms among the competition authority, consumer protection authority, and MCS can ensure the needed data is available to each of them without overburdening FSPs with duplicate data collection efforts. For example, the Competition Authority of Kenya periodically makes inquiries into demand-side competition and consumer protection in the banking sector of Kenya. They signed a memorandum of understanding with the Central Bank of Kenya to establish a framework for mutual assistance and collaboration in a range of issues including overall information sharing, coordinated review of competition issues on emerging banking and payment products, and procedures for joint investigative and enforcement activities.

Financial services providers have strong reasons to monitor the market for signs of consumer risks, distress, preferences, and behavior. FSPs do market monitoring to understand how consumers behave towards them, the overall market environment, and the level of consumer confidence; and to identify changing consumer preferences and sentiments, such as towards technology, delivery channels, competitors, and modes of interaction. For example, FSPs may conduct surveys with the general public or with a set of customers from various FSPs, or analyze publicly available consumer complaints data from the whole sector (sometimes published by MCS) to determine whether the FSP stands out or to identify emerging risks that could affect its own customers. See the Central Bank of Brazil’s ranking of the institutions that received the largest relative numbers of consumer complaints in Portuguese.

Industry associations often produce analytical and statistical reports and newsletters, and may use market monitoring to support their dissemination, research, and education roles. For example, in India the Microfinance Institutions Network and the Sa-Dhan Association of Community Development Finance Institutions publish periodic statistical reports with a range of industry statistics including on access to credit and loan quality. See also an example of industry dissemination of information from the bank association in Peru (in Spanish).

Research organizations and networks set their own research agenda that can support the objectives of other parties, including MCS. Their role is very important because they serve as facilitators conducting in-depth research, and they may even be allowed to use the data collected by the MCS to produce knowledge for other parties. For example, the Social Performance Task Force developed universal social performance standards including key consumer protection principles and gender considerations, and the Microfinance Center facilitated research on compliance with such standards in 12 countries. Also, in 2020 Innovation for Poverty Action launched a research agenda for experimental financial consumer protection work in emerging markets.

International donors and investors want to promote inclusive financial systems, that follow high standards of consumer protection and fair treatment. To do so, they might want to monitor whether the FSPs they invest in and/or support are abiding by these standards, by benchmarking their performance against other FSPs using basic indicators that they could gather through market monitoring activities. They may also want to ensure that FSPs overall are generating positive consumer outcomes, by directly supporting FSPs’ efforts to monitor, measure and assess outcomes, or by supporting MCS’s efforts to strengthen market conduct supervision. The latter may range from foundational support to improve regulatory reporting data quality, to investments in suptech. Market monitoring in particular could act as a reinforcement of the investor’s principles and goals, especially when MCS publicly disseminate the results of their monitoring activities and discuss them with the industry. For example, USAID and GIZ have assisted the Myanmar Consumers Union in using surveys and social media to assess consumers’ main concerns with digital finance, whereas in Cambodia, Mastercard Foundation supported the Center for Financial Inclusion’s Client Voices project to test interactive voice response as a cost-effective and scalable solution to understand consumer risks. CGAP has drafted some recommendations for funders to design impactful data initiatives, to elevate the voice of consumers in market conduct regulation and supervision, and to support market monitoring in digital credit.

Recommendations for funders working with supervisors to elevate the collective voice of consumers

| Existing practices and internal systems | Possible interventions |

|

|

Adapted from “Elevating the Collective Consumer Voice in Financial Regulation”.

In emerging markets, market conduct supervisors typically face significant resource constraints that constrain their ability to undertake consumer protection supervisory work effectively. Such constraints are becoming more severe in the context of fast-evolving digital financial services. In such contexts, the support and collaboration of other financial sector stakeholders can be invaluable in the pursuit of more effective, customer-centric approaches to consumer protection.

Back to top ↑

Back: Introduction | Market Monitoring Tools | Country Cases | Continue: Further Resources