Does Financial Inclusion Impact the Lives of the Poor?

The financial inclusion community has come a long way from the days of anecdotal stories – about “Juanita” becoming empowered or “Haseena” increasing her income from her business – that were used to demonstrate impact on the lives of the poor. In what feels like a bygone era, practitioners used to believe that when customers continued using financial services it meant that financial services were improving their lives. The pendulum has swung wide in terms of the type of evidence that is considered acceptable. Over the past decade, we have seen an explosion of impact research on financial inclusion for the poor. CGAP’s latest effort to synthesize the evidence has uncovered more than 80 new research papers published since 2014.

But what has all this research revealed? We still have naysayers, and we still have proponents making big claims, both using the same research to justify their positions. While CGAP applauds the evolution toward more rigorous evidence, we recognize that there is still something missing: a coherent, nuanced and broader inclusive growth and finance story. What does all of this new evidence tell us about what we should invest in and what promising welfare-enhancing solutions for poor people we should experiment with? Overly simplistic interpretations of the evidence to date are filling the void: credit is bad; savings is good; and insurance is good, but low uptake means it can’t be commercialized for the poor. We are not getting to the level of nuance needed to guide policy decisions. This lack of a clear, overarching narrative is leading to misguided resource allocations among donors and many missed opportunities.

A theory to connect the dots

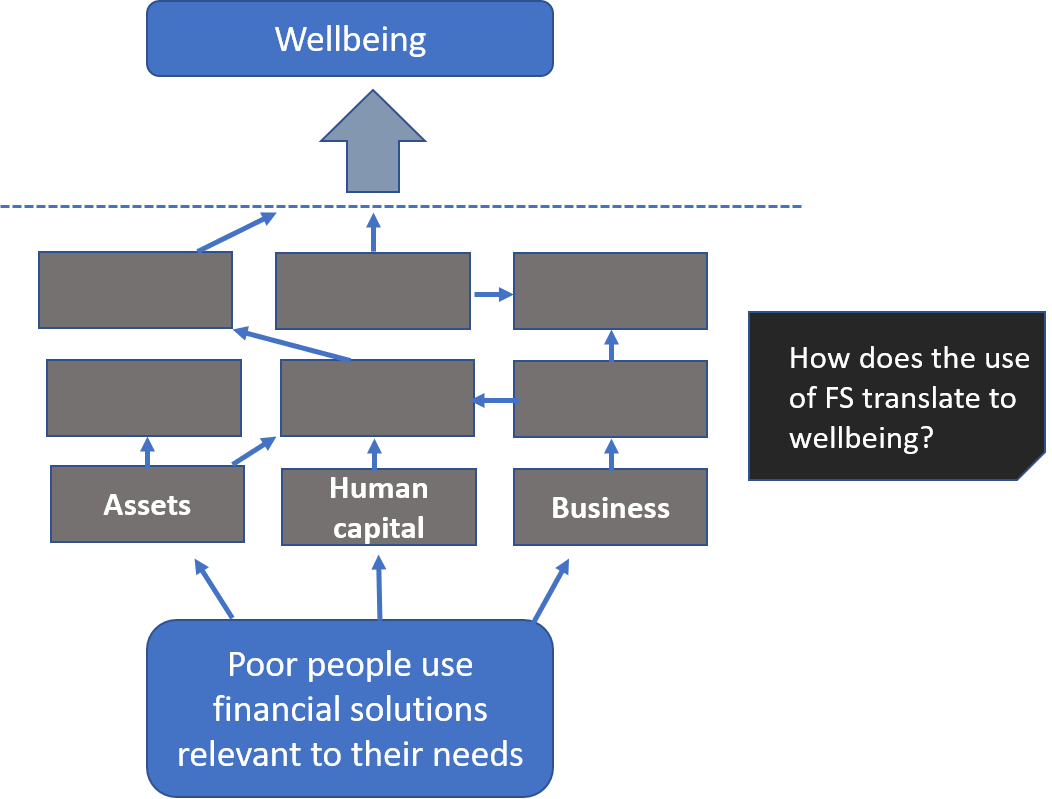

One of the biggest challenges with synthesizing the evidence is the lack of a clear theory of change that explains how access and use of financial services is supposed to improve well-being across different types of people and geographies. The early microfinance theory of change was simple (yet compelling) and focused on a very small subset of the poor – microentrepreneurs. According to this theory, microentrepreneurs are credit constrained and unable to grow without access to credit. Microfinance uses social capital to unleash this credit constraint, enabling microentrepreneurs to grow their businesses, resulting in increased income and reduced poverty. The problem is that this theory doesn’t apply to other client groups like farmers, day laborers or migrants. Because microfinance was commercialized and evangelized for all types of poor people, when evidence started to come out it was lackluster. Not surprisingly, we learned that microfinance only really helps increase income for microentrepreneurs who already have a business.

More recently, the de facto theory of change on digital finance that CGAP and others have been advocating is that by building digital rails, we can reduce transaction costs and unlock business models and product innovations among the private sector to serve poor people. While this is certainly part of the story, it does not explain why or how someone would choose to shift from existing channels that may be working for them, especially if there are high social and transaction costs that may be embedded with the use of the digital channel.

Imagine you are a woman in a village in Zambia and you are part of a village savings and loan association (VSLA). You have a group that holds you accountable for saving every week. The group gives you a network that you can draw on if something happens and you need additional funds. Would opening an account at a bank or buying a phone to set up a mobile money account add value to your life? Would that value be big enough for you to drop out of the VSLA? So far, there is little evidence that for some groups, especially women, formal financial services add sufficient value to shift people’s use patterns. Investing in social networks for the sake of future reciprocity is an important reason why savings groups and other informal channels continue to dominate among certain groups. Digital channels may strengthen social networks, but they have also been shown to reduce them.

None of the prevailing theories for financial inclusion fully explains how greater access and use of financial services improves poor people’s well-being. How does a simple transaction account to send money or pay a bill lead to poverty reduction? It is just as easy to use this transaction account to increase spending on nonproductive things like gambling or cigarettes. How do we know that a transaction account will improve someone’s well-being?

Unless we have a clearer understanding of how change happens from use to well-being, we will continue to shoot in the dark and draw over-simplistic conclusions about impact (or lack thereof) when, in fact, there are many nuances that help explain the mixed results of impact studies. Different groups and different geographies will require different emphases. Not all finance is good, and increased use does not necessarily mean increased well-being. We need a more nuanced story that helps us identify when and for whom financial services may enhance welfare. Part of this clarity requires rethinking well-being itself and clarifying how change happens to get there.

Stay tuned for more

Over the next couple months, we will be sharing our thoughts on the impact narrative in this blog series. We’ll dive into some recent efforts to synthesize evidence on the impact of inclusive finance, discuss our thoughts on emerging narratives like financial health, examine how measuring access and use has been necessary but not sufficient for the impact story, discuss whether we are using the right definition and metrics for capturing well-being and share more about CGAP’s efforts to update the impact narrative.

This post is part of CGAP's "Evidence and Impact in Financial Inclusion: Taking Stock" blog series. The series explores recent efforts to synthesize evidence on the impact of financial inclusion and examines whether concepts like usage, financial health and poverty reduction capture the real impact of financial inclusion.

Comments

Following this series and…

Following this series and looking forward to further insights !

The have a real impact on…

The have a real impact on the communities financial inclusion should be implemented referring to the Basel III definition: “provision of financial services to unserved and underserved customers”. It should be noted that it refers to customers and not people, which means, in our opinion, that an account with a finance provider should be a pre-condition to be beneficiary of whatever credit intervention. In this situation, distinctive Actors applying different sources of capitals & means - accompanied by economic policy instruments - should address the Unserved (poor people). Our OPEN LETTER TO FINTECH is still actual and does confirm the derive of the digitalisation looking at recent outcome in Kenya. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/open-letter-fintech-ascanio-graziosi/. At the end of the day it is a mater to distinguish the role of LENDER, DEVELOPER and PHILANTHROPIST, who have or should have different sources of capitals and interventions as well. In our very recent book we worked out an alternative paradigm " POVERTY: MOVING FROM CREDIT-BASED ECONOMY to COMMUNITY BASED ECONOMY https://www.morebooks.de/store/gb/book/poverty-an-alternative-paradigm/…. The documents/papers released by CGAP, Basel III, Agenda for SDGs and other financial establishment's sources, inspired our work.

Actually, I have a mixed…

Actually, I have a mixed view. Microcredit is very helpful for some but not much for others. May be users behavior could be one among many that affects the impact of the service. It is good to explore more.

Add new comment