Personas Show How Social Norms Impact Women’s Financial Inclusion

This is Hanan. She lives in a large city in southern Turkey, where she has started a home-based catering business. At 46 years old, she has started this business out of necessity. While Hanan has always been fearful of failing as an entrepreneur, she is excited to see her business growing to the point where she is considering financing a new, more efficient oven.

Her husband does not want her to purchase an oven. He tries to remain involved in the day-to-day operations because he does not think she is capable of managing the finances on her own and wants to ensure she does not make risky purchase decisions. Despite gaining confidence by managing her business’ finances and operations, Hanan remains concerned that she will make a costly mistake or, as her husband fears, that the business could fail.

Hanan is also worried that people outside her family will judge her for having a financial account or taking a loan to purchase a new oven for her business, but she will do anything to support her family and secure their livelihood. Despite her concerns, she began looking into banking services. Initially, she was only interested in Islamic financial products, but recently she has been speaking with a trusted bank employee to learn about other types of loans and compare costs.

Hanan is not a real person. She is a composite persona based on over 120 interviews conducted in southeastern Turkey. Yet her story is very real.

It represents the experiences of a subset of women whose multi-dimensional backgrounds and influences impact the way they use financial services. Stories like Hanan’s are often lost when the development community treats “women entrepreneurs” as one homogenous group. Women are sometimes segmented based on limited demographics, the size of their business, or whether they are entrepreneurs of necessity or choice. But within these broad categories, the financial inclusion community must challenge itself to better understand women clients and beneficiaries.

Personas are one way to achieve a deeper understanding and more nuanced segmentation. They can be used to reflect not only important demographic information but also the social norms that influence how women use financial services. Instead of describing women entrepreneurs only in terms of capital constraints or business acumen, for example, this type of persona can situate women within the web of motivations, needs, pain points, backgrounds and influencers that impact their use of particular financial services.

However, personas rarely reflect social norms. Funders often conduct gender analyses before designing financial interventions or products, but few examine the impact of social norms in these analyses or employ social norms diagnostics in financial inclusion programming. Gender analyses may point out low rates of women’s financial inclusion or employment, together with data regarding practices such as early marriage, fertility rates, or sector segregation in employment, to name a few. However, detailing the normative drivers of particular outcomes with a diagnostic is an additional layer.

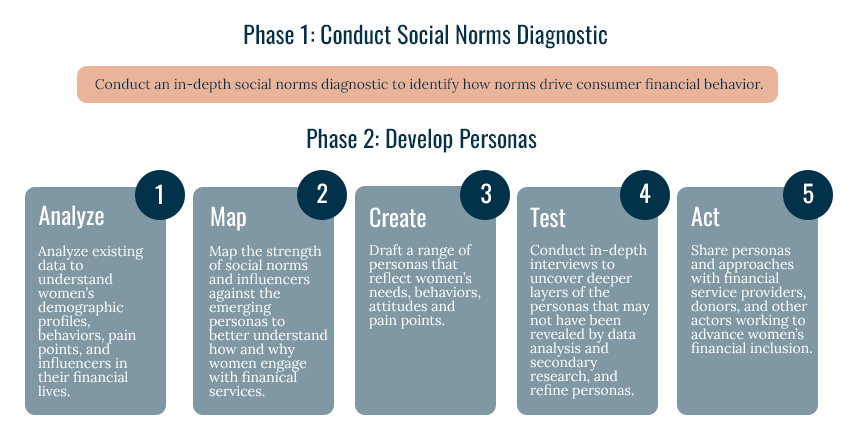

Hanan’s persona is one of four that CGAP designed with this extra layer. To delve into why and how social norms impact women’s interaction with financial services in Turkey, we conducted an initial social norms diagnostic and then followed a five-step process for developing the personas:

Persona Design Process

Through the five-step process, there are some questions that help the designer to understand how social norms impact the designed personas. The first is, “What attributes and characteristics shape the persona?” To answer this question, the designer breaks down women entrepreneurs’ demographic details to define a persona. The second is, “Why does she behave the way she does?” Here the designer tries to define the persona’s motivations, agency, and decision-making capabilities in daily and business life and identify family members and other influencers who impact those decisions. Finally, the designer asks, “How does she behave as it relates to financial services?” Specifically, the designer looks at how the persona accesses and uses financial services and how this influences her financial decision-making. A simple template can help to facilitate this process.

This process can be illuminating. In many cases, program and product designers may realize the effectiveness of not only developing products that better serve women’s needs, but of considering the influence of women’s households and communities when designing products, ancillary services, and marketing campaigns. Women cannot bear the burden of driving social change on their own. Donors are beginning to add gendered social norms into funding strategies and can promote the usage of personas to their partners. To expand their client base, some financial services providers are undertaking marketing campaigns and offering products to nudge public sentiment regarding women’s roles in society where there is a demonstrated willingness by women entrepreneurs to push the boundaries. Finally, where rigid social norms restrict women’s ability to access and use financial services, providers must design workarounds that help women to achieve their goals.

Personas are useful a tool to better understand and build empathy with the women we serve. By including social norms in personas, the financial inclusion community can better understand women’s pain points, motivations and preferences for a range of services, and the interrelated barriers, opportunities, influencers and norms that can affect women’s ability to interact with financial services. We invite you to share your approaches and adaptations of these tools by joining the FinEquity community of practice or sharing your resources in the comments section below.

Resources

Unpacking how social norms impact women's ability to interact with financial services.

Reflections of social norms amongst women Syrian entrepreneurs in Turkey.

Key recommendations to donors and financial service providers.

Add new comment