|

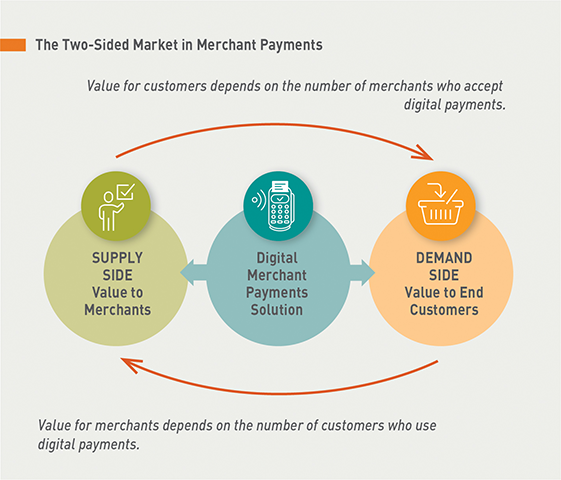

One of the peculiarities of digital merchant payments that makes it more complex than peer-to-peer (P2P) payments is that it is a two-sided market. The two sides—supply and demand—are distinct from one another: they have different reasons for using the service and different needs and preferences.

To a large extent, success in a two-sided market depends on cross-side network effects. The term “network effects” is based on the notion that each user’s perception of the value of the product or service depends on how many other people are also using it—in other words, the size of the entire network. In a business model, cross-side network effects often are reflected in the scaling strategy and basically refer to the concept that every new user added to the service increases the value for existing users. In fact, it often increases the value exponentially, since one new user creates the prospect of new interactions with each of the existing users. For example, two telephones enable only one link between participants: A to B. Adding a third telephone enables two more links: A to C and B to C. Adding a fourth telephone enables three more links: A to D, B to D and C to D, and so forth. Each new participant grows the value of the network more than the last one did.

Conversely, it means that a business governed by network effects can be very hard to get started because the value of the service it provides will be low until a sizable active user base has been established. A business can find itself in a dilemma where it is not able to scale because it is not able to scale. A simple example of a service subject to network effects is P2P payments: the more users are on the payments platform, the more useful the service will be to each user. WhatsApp and Instagram are other well-known examples.

Cross-side network effects mean that the value of the service to a user on one side of the market depends on uptake on the other side of the market. In this case, a merchant payments product is useless for customers unless there is a sizable merchant network in which they can use it. Conversely, unless there is a sizable consumer base already signed up and eager to use the product, merchants will not want to offer it. One side needs to be already in place for the other one to find it worthwhile to join.

Cross-Side Network Effects in Merchant Payments

Unlike traditional network effects, cross-side network effects require providers to scale both sides of the market in a way that generates sufficient momentum and critical mass among merchants as well as consumers. Providers should take this challenge seriously. Getting it wrong could doom the business, whereas getting it right could create a positive feedback loop that rides its own momentum toward scale and success.

Many of the world’s most successful technology companies have succeeded partly by deftly leveraging two-sided network effects, these include Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook, and Uber. As a result, merchant payments providers in emerging markets and developing economies can tap into a large and growing base of research, industry lessons, and best practices. One useful resource is the NfX “Network Effects Bible.”

The following is a look at some of these best practices and their implications for important decisions providers have to make.

Product

The most fundamental implication is that providers need to have a genuinely compelling value proposition for merchants as well as consumers because the two sides of the market are equally important but want different things. A payments mechanism alone is unlikely to be sufficient because cash already works quite well for both sides in retail commerce. To be successful, merchant payments providers may need to offer a combination of value-added services and loyalty rewards that cash cannot compete with. For more on what a compelling value proposition for merchant payments might look like, see “Value Proposition.”

Some companies build up one side of the market ahead of time by first offering a solution that responds to the needs of users outside of the core product. This could be closely or only loosely related to the core product itself. A simple example would be to build till software through which merchants can record cash transactions or an inventory manager through which merchants can easily restock from their suppliers. A provider that manages to get uptake on such a solution before launching the merchant payments product may be able to establish a vast merchant network from day one. For a few detailed concepts of value-added services that providers could offer, see “VAS Playbook.”

Another approach is to ask only one side of the market to change the way it normally does things. Getting traction with a new product is always difficult if it requires users to change their behaviors in some way—the greater the change required, the greater the challenge. In the case of merchant payments, this problem is doubled because there are two user groups that need to be persuaded. Each group has various ingrained behaviors and business processes that it will consider changing only if it has a truly compelling reason. Hence if the provider is able to let one side to the market continue doing what it’s always done, the challenge is cut in half. One example of this is the payments market in the United States, where players that enabled merchants to simply accept cards in a more efficient way have gotten significantly greater traction than those that require consumers to use new types of accounts or acceptance technologies. For an overview of the trade-offs around acceptance technologies, see “Acceptance Technologies for Merchant Payments.”

Go-To Market Strategy

In thinking about how to take the product to market, providers should focus on scaling the side that will be harder to bring on board. The premise is that if it’s easy to get consumers excited but hard to get traction among merchants, then all those excited customers will quickly be disappointed by the lack of acceptance points and the product may never recover. If so, providers will want to focus on building out the acceptance network before promoting the product to consumers. Conversely, if consumer behavior is difficult to change but merchants are quick to follow market trends, then providers should focus on driving the demand side. The latter is arguably the case with credit and debit cards, where issuers have successfully built up consumer demand to the point where merchants find it very difficult not to participate. Note that, for digital solutions in developing economies, it may not be obvious what dynamic will define a particular market. The bottom line is that both sides—supply and demand—need to see clear value in the product.

Although network effects grow stronger with scale, they can also be strong in small subsets of the network. For example, it is clearly easier to generate market momentum and critical mass if you focus the go-to-market effort on a limited geographic area. A natural choice would be the nation's capital or main commercial centers of activity. In early stages the area could be as small as a certain portion of the city. By dedicating a given amount of effort and capital to a smaller area, providers can more easily achieve the ubiquity of the acceptance network and the saturation of the consumer side that yields critical mass. Once market momentum builds in that area, the provider can gradually expand.

Aside from geography, a well-targeted roll out can also build critical mass in a specific segment of the market, even if that market is small. One way to do that is to focus on specific value chains and ensure that the product works for a variety of use cases across the chain. For example, focus on taxi drivers—providers can enable them to not only accept payments from consumers, but to pay for fuel, insurance, taxes, traffic fines, and leases through a convenient solution.

By creating compelling use cases for each of the other participants in that ecosystem, payments providers can build critical mass around that segment without the scale needed for a general mass market play. An even simpler example is to consider distribution chains for fast-moving consumer goods. By aggressively partnering with distributors, payments providers can enable merchants to easily spend the electronic money collected from consumers on restocking inventory, which is one of their primary uses for revenue. Enabling the same distributors to also use digital payments within their operations would help providers build more positive feedback loops in this market segment.

Another common feature of successful two-sided markets is that users can participate on either side. For instance, users of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, or eBay can create and consume content on the platform. Consumers all over the developing world are increasingly selling things informally and marketing them digitally over social media. By building solutions that enable consumers to also be merchants, payments providers can create powerful new reasons for people to switch away from cash. This is partly how Alipay and WeChat Pay have managed to shift the massive Chinese market in just a few years. (For more on this, see “China: A Digital Payments Revolution.”)

Distribution Strategy

Providers who balk at the scale and speed required to establish sufficient networks on either side of the market should consider engaging with partners who can bring participants—merchants or consumers—into the network. Wallet providers may want to partner with large retail chains like supermarkets or gas stations—or even government entities, including schools and health clinics. Unfortunately, in many developing countries, retail chains tend to be small and there are few of them.

Another way to expand the network directly through partnerships is to enable interoperability with other payments providers, which can in one stroke substantially expand the networks on both sides of the market. Given the powerful network effects in merchant payments and the difficulty even large providers have had in building critical mass by themselves, interoperability may be necessary for many or most providers in developing markets. For more information, see “Interoperability: Why and How Merchant Payments Providers Should Pursue It.”

There are also indirect ways to expand the network through partnerships, such as by licensing a solution cheaply or even giving it away for free to companies that aim to acquire users. One example is the Android operating system, which Google made free and open source for handset makers, resulting in a massive expansion of the Google user base worldwide. In terms of merchant payments, providers can similarly license or make their source codes freely available to third-party merchant acquirers, who then automatically expand the provider’s acceptance network as they go about building their own business.

In markets with a weak or nonexistent merchant acquiring space, this could involve well-developed solutions that third parties can brand as their own—making it easy for new merchant acquirers to enter the market. This may be the quickest way for providers to build a large-scale acquiring network without having to invest the time, effort, risk, and capital itself. In markets with strong existing merchant acquirers, open APIs can make it easy for those partners to integrate and build value-added solutions on top of the payments platform.

Revenue Model

A common strategy in developing two-sided markets is to provide some form of subsidy to one side of the market. This can prove worthwhile if that side of the market is particularly challenging to develop and/or particularly important for the overall value proposition in the network. For instance, many ride-hailing companies pay drivers more than they earn in the initial stages of developing a market to ensure that consumers can always find a ride.

For merchant payments, this commonly applies to the consumer side of the market. Credit card issuers actively subsidize consumers through various perks, loyalty rewards, cash back schemes, and so forth. Their assumption is that consumers have the most influence on which payments instrument is used for the transaction. While this is probably true, it does not mean merchants have no influence, as demonstrated by CGAP research on mobile money merchant payments specifically. For a comprehensive overview of loyalty models in retail commerce and ideas for digital payments providers, see “Loyalty models can create value for consumers".

One way to subsidize participation in the network without incurring a direct cost is to pass on savings generated in the network. For instance, if digitizing payments across the distribution chain of consumer goods reduces costs on the supplier side, payments providers could negotiate a discount on inventory for merchants participating in the network. This could prove a powerful monetary incentive for merchants to join, while not incurring any direct costs for either the payments provider or the supplier.

Customer Engagement

Finally, building a strong and committed user base is not only about product, price, and incentives. Many companies devote a lot of effort into building a passionate community around their brand, their product, and the lifestyle they aim to embody. By thoughtfully engaging with their customers—and encouraging their customers to engage with the company and with each other—providers can sometimes create a vibrant community.

For example, providers may offer tools, classes, and learning opportunities to merchants to help them to advance their businesses. This type of engagement can create a powerful sense of buy-in and enthusiasm around the payments product.