How do financial services impact the lives of poor people? Though the global development community has debated this question for decades, we seem to be no closer to an answer today than we were when we started. A growing number of rigorous studies meant to clarify the impact debate have instead produced mixed — seemingly contradictory — evidence. This has resulted in both advocates and critics citing rigorous evidence when arguing for or against the prioritization of financial inclusion in the global development agenda. While several narratives have emerged over the years to describe the role of financial services in poor people’s lives, their over-simplifications prevent us from making sense of the mixed results observed across impact studies. What is clear is that the financial inclusion community needs a more nuanced, evidence-based impact narrative to make holistic sense of existing research and help shape more effective financial inclusion policies.

The various narratives that underlie today’s impact debate reflect the evolution of financial services for the poor. The first impact narrative came out of the microfinance industry in the 1990s. It encapsulated the aspirations of leading microfinance institutions to offer small loans to families and micro-businesses as pathways out of poverty. As a wider variety of financial services proliferated in emerging markets, a broader narrative took hold around the idea that greater access to and usage of a range of financial services not just loans can empower poor people. Next came the digital revolution with a narrative describing how digital financial services were a game-changer that could lower the cost of connecting excluded groups to the formal financial system. Today, new narratives continue to emerge around specific technologies and business models, such as pay-as-you-go (PAYGo) asset finance and fintech.

It is important to remember that the primary purpose of these narratives was to express the aspirations of pioneering organizations in financial inclusion and to reflect what the community knew at the time - not to rigorously prove the impact of financial services. Historically, these narratives have helped to develop a sustainable financial industry for low-income customers and can hardly be blamed for failing to answer the impact question.

Today, we have a completely different situation. The body of evidence has grown significantly over the last 15 years, providing data points on the impact of various financial products on people’s lives. However, we lack an evidence-based framework that makes sense of the data and explains how impact happens (or does not happen) for different people in different contexts. In retrospect, the research community’s focus on documenting the average impacts of specific financial products on large groups of people has led many to overlook the individual and contextual factors that alter impact from one customer, provider or country to the next. This lack of nuance and contextualization has made it difficult to explain why rigorous studies report seemingly contradictory impact estimates for similar products around the world. It has also made it challenging to extract actionable lessons for policy makers on how financial services can improve people’s lives.

New theory of change

CGAP believes that it is time to move beyond the existing narratives supported by some and critiqued by others. Based on an analysis of the growing body of evidence and multi-stakeholder consultations, CGAP has developed a theory of change (TOC) to guide the financial inclusion community toward an updated narrative that shows the many ways financial services can impact the lives of poor people. To do this, we took as our starting point a different question than the one we saw in most of the existing impact research. Instead of starting with a financial service and asking, “What does this service do for poor people?” we asked, “What outcomes would poor people like to achieve?” Starting with this question led us to think more holistically about the goals low-income people set for themselves and whether or not financial services play a role in achieving them.

When it comes to understanding the overall impact of financial services, a TOC offers several advantages over the log-frames and logic models that researchers have typically relied upon in their assessments of individual programs or financial products. A logic model is a linear depiction of how a program’s inputs (interventions) translate into outputs (services delivered) and outcomes (changes experienced by a program’s beneficiaries). By contrast, a TOC depicts multiple pathways to an outcome. It seeks to capture all the factors that influence an outcome rather than only those that are the focus of a particular program or product. Furthermore, a TOC explicitly acknowledges its underlying assumptions. CGAP believes that moving beyond logic models and developing an evidence-based TOC for financial services will make it easier for the financial inclusion community to identify gaps in our understanding of how change happens for poor people and assess where more evidence is needed on the role of financial services.

A TOC starts with a basic question: “What is the ultimate impact on people’s lives?” In constructing a TOC for financial services, CGAP was confronted with the fact that most of the existing narratives have set poverty reduction as their ultimate goal. Existing evidence does not prove that financial services always reduce poverty. Furthermore, there is a growing awareness that financial services cannot be expected to generate the same results everywhere. Whereas clean water, mosquito nets and vaccinations do the same job in the same way for everyone, financial services are essentially tools that people can use differently to achieve their own goals. By their very nature, they align less with a universal standard like poverty reduction and more with Amartya Sen’s concept of capability, which says that the ultimate development outcome is defined by the individual.

Recognizing that concepts like poverty reduction are too narrow in scope to encompass the ways in which people define and aspire toward a higher quality of life, CGAP adopted the concept of “well-being” to describe the ultimate outcome sought by poor people. Well-being goes beyond the monetary and consumption-based measurements of poverty reduction on which many financial inclusion impact studies continue to rely. It includes other dimensions like socialization, health and education that factor into people’s life goals. Anchoring a TOC in the concept of well-being allows the financial inclusion community to better understand the ways in which individual and contextual circumstances affect the impact of financial services. It also allows researchers to hypothesize a variety of impact pathways, beyond monetary measures of poverty reduction.

Updated theory of change for financial services

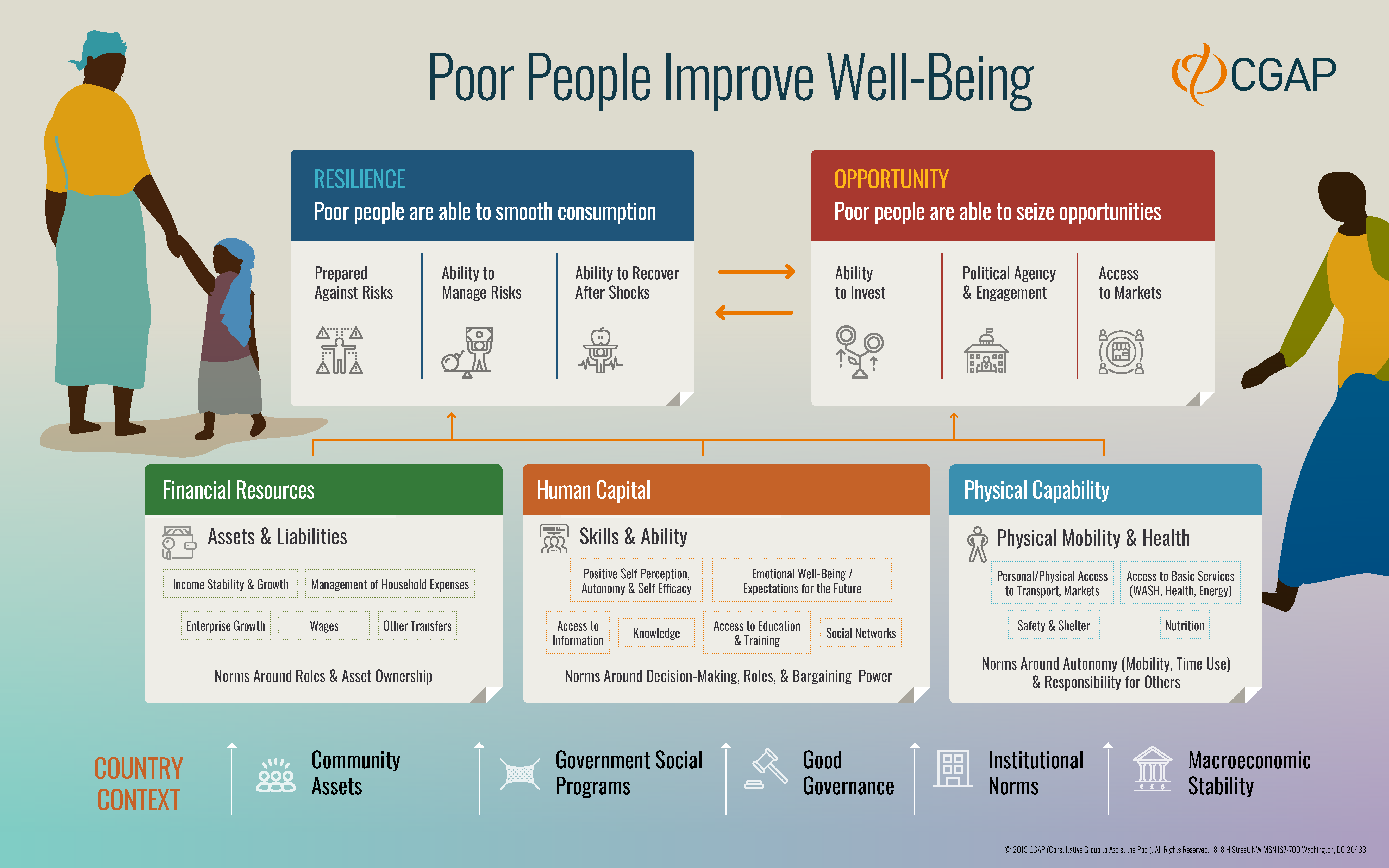

Next, CGAP focused on identifying outcomes poor people strive to achieve to improve their well-being and reviewed the literature to assess whether there was evidence that financial services contributed to these outcomes. Our review revealed that evidence for the role of financial services clusters into two high-level outcomes:

- Building resilience refers to how financial services allow people to prepare for shocks, deal with them when they occur and recuperate afterwards.

- Capturing opportunity refers to the ways financial services help people to take advantage of opportunities in a broad sense, whether investing in a business, getting an education, migrating or receiving medical treatment.

These outcomes reinforce each other in a virtuous cycle: more of one leads to more of the other. Taken together, they give the financial inclusion community a wider lens through which to examine the impact pathways of financial services. By acknowledging that these outcomes have pre-conditions related to financial resources, human capital, physical capability and country context, we can start to hypothesize how the impact of financial services changes when some of those pre-conditions are lacking for any individual.

Impact evidence vs. measurement frameworks

Most efforts to measure the effects of financial inclusion interventions in recent years have started from the bottom up; that is, they have started with a financial service, determined the most likely need or purpose that people have for using that service, and then assessed whether the service is meeting that need. They focus on capturing what is likely to happen when people use a certain financial product. Examples of this approach include the needs framework developed by i2i, the Financial Health Network’s measurement framework on financial health, and the measurement framework developed by BFA and UNCDF.

Bottom-up approaches may tell you how people are using specific financial services and whether they lead to certain outcomes. On their own, however, they do not reveal much about how change happens or why it happens differently in different contexts. For example, a bottom-up analysis might show that a savings product improved some people’s ability to meet daily household and business expenses, but it does not explain why this happens for some people and not others or whether it affects people’s overall well-being.

Since CGAP’s focus has been to articulate an impact narrative, we took a top-down approach starting with the concept of well-being to enable the financial inclusion community to be more holistic in our understanding of how change can happen for poor people. We did not assume that financial services must be part of change. Financial services are not used in a vacuum. Understanding not just the causal pathways between financial services and impact but the dynamic interplay between all the relevant factors — from the person’s distance to markets to the prevailing social norms — will go a long way toward setting realistic expectations for the role financial services play in advancing well-being.

The challenge now becomes how to reconcile these two approaches. On the one hand, can we say anything about impact using bottom-up approaches? On the other hand, can the top-down TOC approach actually be measured? What we know for sure is that the bottom-up measurement frameworks on their own do not establish the impact of financial services on poor people. In fact, as UNCDF and BFA note in their work, impact evidence is required to test the validity of the hypotheses generated through the bottom-up approach. As to whether the top-down TOC approach can be measured, there is a need for more experimentation. It is an open question whether it would be more effective to measure self-identified goals set by poor people, a la Amartya Sen, or to agree on a universal set of metrics that approximate well-being.

At this stage, what is clear is that there is a need to better align the impact evidence with the metrics used to measure progress in our field. The financial inclusion community should not be prioritizing indicators that have no correlation to impact. For example, while we know that expanding access to basic accounts is a desirable step toward financial inclusion and, therefore, we measure progress on this front, we also know that simply expanding access does not improve well-being in a significant way. This means that account access indicators are not good indicators of higher welfare benefits for poor people.

What does the TOC tell us about the impact narrative?

The process of constructing an updated TOC for financial inclusion has left CGAP with several takeaways.

- Improving well-being requires both resilience (stabilizing consumption despite shocks) and opportunity (making investments that transform livelihoods), and these two aspects of well-being are mutually reinforcing. Resilience is the foundation for poor people to achieve the stability from which they can build their lives. Resilience enables people to capture welfare-enhancing investment opportunities. When captured, these opportunities in turn reinforce people’s stability, helping them to better manage risks and cope with shocks and allowing them to capture even more welfare-improving opportunities. Resilience improves opportunities, which improve resilience, and so on in a virtuous cycle. Therefore, both are critical to improve, rather than just maintain, well-being.

- Resilience reduces the stress of uncertainty and risk in poor people’s lives. This opens up space both mental and financial to make investments that are riskier but potentially more rewarding in the longer term. One of the most important functions for financial services is to build people’s resilience.

- A person’s ability to capture opportunities that improve their well-being is powered by financial resources, human capability and physical capability. Financial services play a role in all three of these areas. They contribute to financial resources primarily by helping poor people to increase and diversify their incomes while managing household expenses. They can support human capability by enabling people to invest in their education and social networks, which can in turn contribute to higher levels of self-efficacy and better expectations for the future. In the realm of physical capability, financial services enable investments in basic services such as water, sanitation, shelter, energy, and health.

- Well-being is not only driven by individual decisions. It requires conditions at the community and national levels that reduce risk and create opportunities. Communities and governments play an important role in creating the conditions in which poor people can prosper. They must ensure the availability of basic services like education, water and sanitation, health care. They are also critical for creating the general conditions, such as the investment climate, political freedom, and rule of law, that allow enterprises to thrive and create decent jobs. After all, opportunities must exist before poor people can capture them.

What next?

The TOC suggests several priorities for the financial inclusion community in the future.

- Scale up the financial services that contribute to resilience. Evidence suggests this can be achieved by expanding digital payments to rural areas and places that are prone to natural disasters. Also, by improving the business model economics for insurance, including using subsidies to design products to fit needs and enable take-up by important segments at scale.

- Revisit enterprise finance. There is no denying that enterprises are an important part of the equation for development. The evidence tells us that enterprise finance, including credit lines, insurance, and guarantee facilities, is critical when firms are capital constrained. We need to reach enterprises with financial services in ways that enable them to make growth-inducing investments – and not only by providing consumption credit for businesses. We also need to revisit the use of subsidies and explore whether there are better ways to incentivize providers to take greater risks to serve or employ lower-income groups and have a greater impact on firm growth.

- Prioritize financial services that improve human capability. Beyond focusing on school payments, the financial inclusion community has not done enough to explore how financial services can improve access to education and skills development. Adapting to changes in the world, whether the digital economy or climate change, requires people to continue to re-skill and re-tool. It requires investments in both traditional and non-traditional education. It is also worth thinking more about the ways in which government subsidies could be used to facilitate more innovation and risk-taking in financing the education and skills development space.

- Prioritize financial services that improve access to health and welfare-improving basic services, such as water, sanitation, and housing. CGAP and others have worked to unpack the PAYGo business model and how it can be used to facilitate access to lighting and energy; however, we need to do much more to extend this work to other services, such as water and sanitation. Other services may not be readily solved with commercial models like PAYGo that enable households to buy a simple asset. But the financial inclusion community should not shy away from working with the public sector to explore how financial services can contribute to government-led approaches to expanding the reach of water, sanitation and housing to poor communities.

- Design public policy that distinguishes between contextual preconditions at the individual and community level that enable financial services to empower different groups of poor people. Donors and researchers should invest in better research methods to identify how contextual variables determine the impact of financial services on people’s lives. This will shed light on important program complements to financial inclusion initiatives and features that could make financial products more beneficial for different customer segments.

This is an exciting time to reimagine how financial services can improve the well-being of people living in poverty. CGAP hopes that its work to create a TOC and updated narrative for financial inclusion will motivate those working in inclusive finance to push beyond the artificial boundaries that we have put on the financial inclusion field and expand our research to other areas where financial services can have an impact on poor people’s well-being.

This essay was written by Mayada El-Zoghbi, who led the evidence and impact work at CGAP and now is managing director of the Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion. Emilio Hernandez, Matthew Soursourian and Elizabeth McGuinness also contributed toward this essay.